The Royal Regiment of Artillery

The British garrison was stationed in Québec City from the Conquest until the troops left in 1871. Soldiers were a familiar sight in the region, especially in Upper Town and within the city walls. Their presence impacted the city’s economy, land use and even influenced local leisure activities. The people of Québec City encountered soldiers on a daily basis, particularly during military parades and drills, which often took place at Artillery Park and on the Plains of Abraham.

- 112 years of British military presence

- 1500 average of soldiers stationed in Québec City

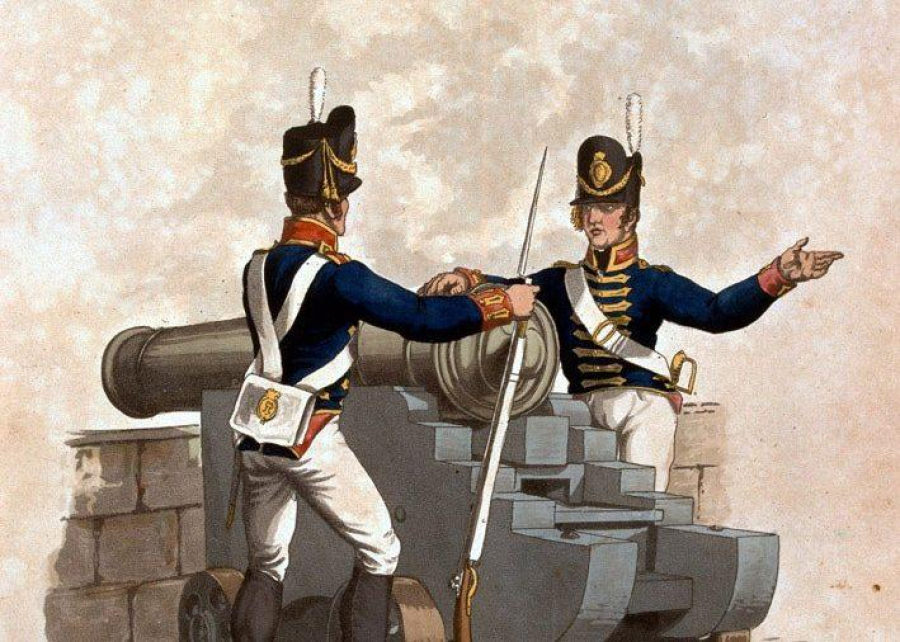

The Royal Artillery was one of the regiments tasked with defending Québec City throughout this time. It was the main regiment responsible for operating cannons and other artillery. The handling of artillery required specific skills and demanded specialized knowledge, quite different from those needed for infantry. Anyone hoping to rise through the ranks of the Royal Artillery had to complete a two- to three-year course at Woolwich College in England, where they would learn the theory and practical aspects, including studying subjects in mathematics such as geometry and trigonometry. One of the notable products of this education was James Pattison Cockburn, an artillery officer and renowned watercolourist who painted several scenes of Québec City in the 19th century.

To protect Québec City from the American threat during the War of 1812, four Martello towers were built on the Plains of Abraham. These towers were among the locations where soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Artillery were stationed.

Recruitment

When a man enlisted in the British army, he was approached by a recruiter, usually in Great Britain, but sometimes in the colonies, including Canada. He had to be between 18 and 25 years old and in good health. For artillerymen, the minimum height was 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 metres), which was slightly taller than for infantry soldiers. The army sometimes relaxed these requirements to recruit more men during active wartime.

The story of Alexander Alexander’s enlistment, 1801

After drinking his Majesty’s health, […] the sergeant asked me to go to a surgeon, who lives in the High Street, to be examined. […] I was afraid I would not pass and felt a gleam of satisfaction when the surgeon pronounced me a fine, active, healthy young man, able for service.

There were many reasons why someone might choose to join the army. For most, it offered a certain stability: It provided clothing, a steady income, housing and the hope of promotion. Their status also allowed them to travel across the British Empire, an opportunity not afforded to most civilians in the 19th century. However, the pay for a common soldier was low, especially since the army deducted amounts for rations, clothing, weapons and other mandatory expenses.

Soldiers typically enlisted for several years, with the length of service varying from a few years to a lifetime commitment. They frequently moved around, alternating between cities and more remote locations to prevent them from settling down and becoming attached to any one place.

By enlisting, they gave up some of their freedom. They had to ask for special permission to marry or to bring their family to Canada if they had one. Women who accompanied the army often took on tasks like doing laundry and caring for the sick, in exchange for half rations.

Life of the soldiers in the Martello Towers

A soldier was usually stationed in a Martello tower for a month. He brought enough provisions to last the whole period; the tower’s occupants had to be able to withstand a siege for 30 days.

The soldiers did not have private quarters. Their living space was limited to the barracks, on the main floor of the tower. This was where they cooked, ate, slept and spent part of their free time.

They pooled their rations to prepare meals. The regiment provided a large cooking pot and a serving ladle. Each soldier had to bring his own utensils: a plate, a cup, a spoon and a knife. Food rations generally included salted meat, flour, a little butter or cheese, dried peas, rice or oats.

These “salted rations” were imported from Britain. They were sometimes replaced with fresher food, such as bread or fresh meat, when available. If soldiers wanted vegetables, they had to buy them themselves out of their pay. They typically shared two meals a day at the long table in the barracks. Eating very few fresh fruits and vegetables, combined with the cramped conditions in the towers, often led to illnesses such as scurvy.

Soldiers fetched water from wells near Towers 1, 2 and 4. Tower 3 had no nearby well, so they had to bring in water from farther away. Although rainwater was collected in tanks in the basement of the towers, this stagnant water was only to be used during a siege for cooling the cannons.

The barracks floor was lit by oil lamps hung on the walls and had a fireplace for heating and cooking. The vaulted ceiling was supported by a large central column, where soldiers rested their rifles when not in use. They slept in two-tiered bunks. The regiment provided a straw mattress, replaced once a year, and a grey wool blanket. Each soldier had to carry a haversack with labelled personal belongings and take care of his uniform.

Leisure activities were limited to playing cards, dice and dominoes, and drinking alcohol. Alcohol-related incidents were the most common cause of misconduct among soldiers stationed in Québec City.

Part of the soldier’s day was devoted to military drills and various tasks. In summer, there were three shifts; in winter, only two. Curfew was at 9 p.m. in winter and 10 p.m. in summer.

Along with weapons drills and battalion manoeuvres, artillerymen also practised cannon firing. Their duties included maintaining the cannons. A captain visited the tower once a week to check whether the ammunition was ready and whether the cannons and their carriages were in good order. Artillerymen often had other jobs in addition to their military duties, which gave them à a little extra income.

Discipline

As one might expect, discipline was of vital importance in the army. Breaking the rules led to harsh punishments designed to discourage fellow soldiers from doing the same. Minor offences could result in extra duties or restrictions on leave. A soldier caught drunk on duty or showing disrespect to a superior could be sentenced to hundreds of lashes. For more serious offences, punishment could include imprisonment, deportation or even death. During wartime, penalties were even more severe.

Today, as you walk across the Plains of Abraham, you might spot soldiers in blue and red uniforms—these are the guides and interpreters of the National Battlefields Commission, who bring the lives of 1814 soldiers to life for school groups from Quebec and beyond!