The Plains of Abraham, the Focus of Quebec City’s System of Defence

From the time of Quebec’s founding, the French placed emphasis on the defence of the new settlement. Although rather modest in the 17th century, the city’s defensive system was improved over time, making Quebec a real fortified city by the 19th century. In order for the system to be effective, it must benefit from the natural advantages afforded by the local topography. Chief among these were the Quebec promontory, and especially its highest point, the Plains of Abraham.

Quebec was officially recognized by UNESCO in 1985 as a world heritage city, a distinction owed in large part to the preservation of its fortifications.

From the time of Quebec’s founding, the French placed emphasis on the defence of the new settlement. Although rather modest in the 17th century, the city’s defensive system was improved over time, making Quebec a real fortified city by the 19th century. In order for the system to be effective, it must benefit from the natural advantages afforded by the local topography. Chief among these were the Quebec promontory, and especially its highest point, the Plains of Abraham.

The French fortifications

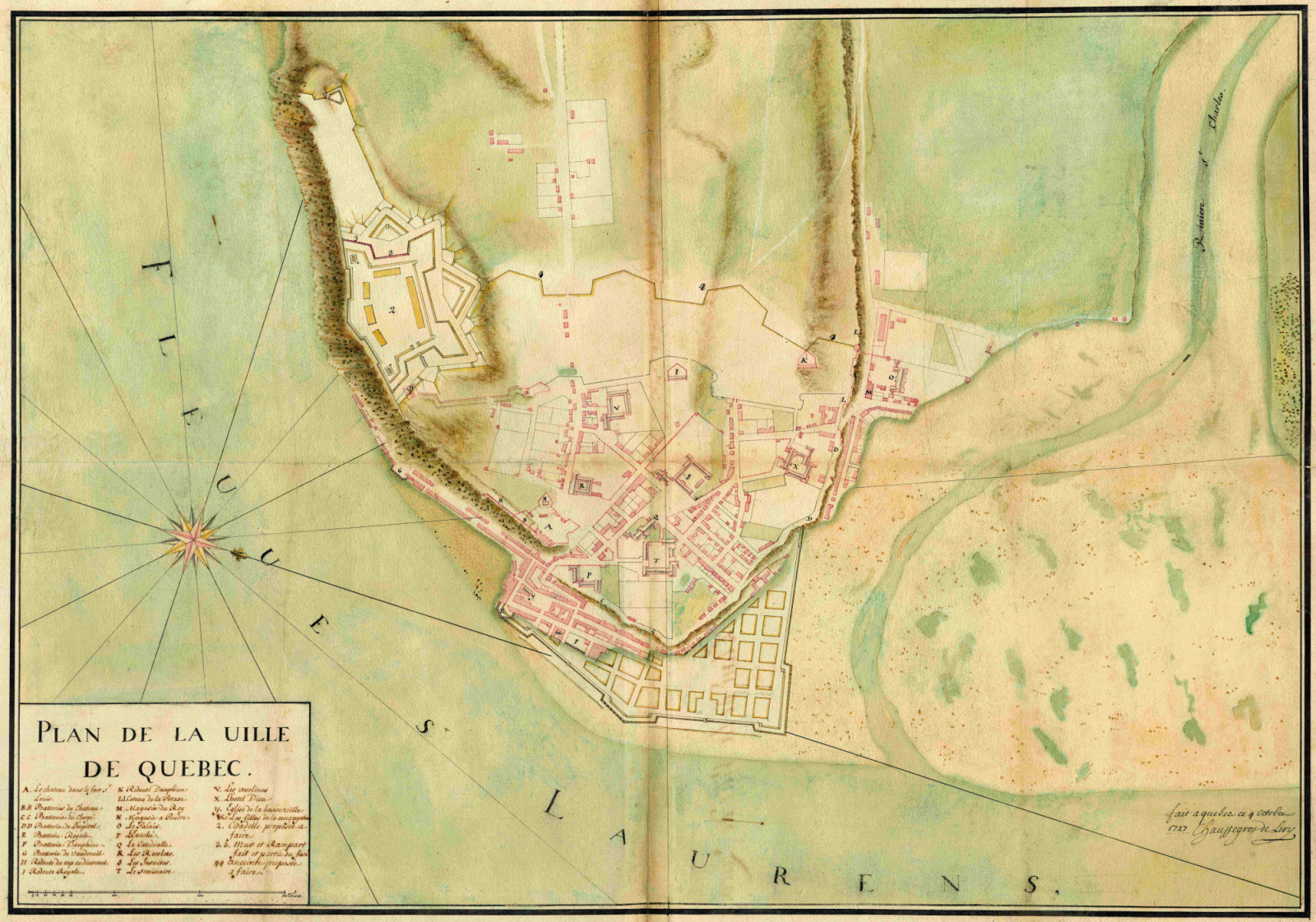

The first fortification works on the Quebec promontory date back to the late 17th century. The first enceinte, a wood palisade flanked by a few stone bastions, was built in 1690 to protect the city’s west flank. Three years later, with an impending British attack rumoured, Governor Frontenac and Intendant Champigny authorized the construction of a second enceinte:

The original wood enceinte was replaced by a masonry wall; a redoubt was built on the shores of the Saint-Charles River, and another on the heights of Cap Diamant.

The works, supervised by le chevalier Boisberthelot de Beaucours, were found wanting by Jacques Levasseur de Neré, the colony’s new engineer, who landed in 1694. He felt that the fortifications should not have been constructed on this side of the heights of Cap Diamant. The engineer also felt that the redoubt on the heights was insufficient to keep an enemy from occupying this strategic location. Levasseur would therefore attempt to correct the errors in Beaucours’ works by constructing retrenchments atop the Cape and starting work on a new enceinte.

1716 saw the arrival of a new king’s engineer, Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry. He would hold the position until his death in 1756. During his career, he proposed a number of plans for Quebec’s fortifications, including, during his first years in the colony, the construction of a citadel on the heights of Cap Diamant. This proposal was shelved for lack of funds and unwillingness on the part of France. Under Maurepas, Secretary of State of the Marine from 1723 to 1749, the Conseil de la Marine strategy for the defence of the colony was focused no longer on the capital only, but on Louisburg and Montreal as well. France was now funding the fortification of these two cities, at Quebec City’s expense.

However, the situation changed in 1745, with the fall of the Fortress of Louisburg to the British. Panic stricken, Quebec City residents pressed the governor to improve its defences. An assembly made up of the governor, the intendant, the senior officers, the bishop and a few business representatives decided to build a new enceinte. Chaussegros de Léry drew up new plans incorporating the bastions constructed by Levasseur de Néré on the heights of Cap Diamant. He also proposed the construction of a citadel, but unsuccessfully. The decision to begin these works was taken without the knowledge of the metropolitan authorities, who had no choice other than to approve them and fund them in part. The remainder would be left up to the colonials.

Léry’s enceinte still had not been completed in 1759, on the eve of the siege of the city by General James Wolfe’s troops. A number of factors, including haste and insufficient planning, cost overruns, and changes of plans while the project was under way accounted for these delays. In any case, this fortification was not a critical factor in the defence of the city in 1759. On the contrary, once the British took the Heights of Abraham on the morning of September 13, the city became highly vulnerable, if not indefensible.

The British fortifications

Having moved into the city in the wake of Quebec City’s capitulation on September 18, 1759, the British conducted an inspection of the fortifications. This task was assigned to engineer Patrick Mackellar, who took note of the poor condition of Chaussegros de Léry’s enceinte, partly because it was not yet complete. In 1760, Governor James Murray ordered the completion of the ramparts and the construction of a series of seven blockhouses on the promontory. The governor also proposed the construction of a citadel, but, as in the case of his French predecessors, headquarters denied funding for the project.

The British understood very early the importance of occupying the Heights of Abraham. Confirmation of this came when the Americans decided to set up their camp and batteries there during the 1775–76 invasion of Canada. Although a failure, the American attack moved the colonial authorities to rethink the city’s defensive system. Frederick Haldimand, the governor of Canada from 1778 to 1786, had a topographic map of Cap Diamant prepared. Mindful of the costs involved, he hesitated between temporary wooden works and permanent masonry works. Although opposed by the engineers, the first option was chosen.

The work began in 1779 under the leadership of engineer William Twiss. Batteries, redoubts, retrenchments and bastions were constructed on the Quebec promontory. However, the most remarkable aspect of Twiss’s works was the construction of a sophisticated citadel, the temporary citadel, on the heights of the Cape, integrating the French works and in particular the bastions of the Ice House and the Cape.

Owing primarily to the lack of specialized labour and the rigours of winter, Twiss’s works proceeded very slowly and were even interrupted in 1783 by the signature of the Treaty of Versailles between England and the United States. While the treaty ended the hostilities, the respite was short-lived. The political situation in Europe and America revived tensions between the British and the French on the one hand, and the British and the Americans on the other. This led the colonial authorities to take a fresh look at the city’s defensive system. But one thing remained unchanged—the strategic importance of the Heights of Abraham.

Gother Mann, the engineer responsible for upgrading Quebec’s fortifications in the late 18th century, proposed the following four-point plan:

Build a rampart completely enclosing the Upper Town, not just its western flank;

Occupy the Heights of Abraham;

Protect Chaussegros de Léry’s enceinte using auxiliary defensive works;

Build a citadel.

Like his predecessors, Mann did not receive the funds needed to fulfill his ambitions. However, before leaving Canada in 1804, he did build a few powder magazines and the Prescott Gate on Côte de la Montagne, and repaired Léry’s enceinte. His plans were not forgotten; on the contrary, they were used during the first three decades of the 19th century to make Quebec a bona fide fortified city.

The threat of an American invasion was again instrumental in renewing the project to fortify Quebec in the early 1800s. Because of Napoleon’s continental blockade in Europe, London found it necessary to turn to Canada for its source of lumber and even ships. Thus the defence of the colony was crucial. It would take more than 25 years to complete Mann’s plans. The first step was raising the ramparts around the upper town, atop the cliff. Without waiting to hear from London, Governor Craig gave his consent to the construction of auxiliary works in the channel in front of the St. Louis Gate and to the erection of four Martello towers. Construction on the towers began in 1808 and was completed two years later, with the exception of the fourth tower, which was not completed until 1812. Finally, construction on the citadel began in 1820 and was completed in 1831, after which only the auxiliary buildings (the hospital, the prison, etc.) remained to be constructed.

From the founding of Quebec City to the middle of the 19th century, the Plains of Abraham was a site of strategic importance in the defence of the city. Overlooking the city and the river, the main avenue of communication, it was seen by the colonial authorities, both French and British, as the key to Quebec City’s defensive system, even though their plans for it were kept in check by cost and labour considerations.

From its modest beginnings under the French regime, the Heights of Abraham underwent considerable development under the British, who constructed numerous blockhouses, the temporary citadel, four Martello towers and the permanent citadel. Excavations were started in the summer of 2006 and have continued in 2007 for the purpose of restoring the remains of one of the seven blockhouses, situated on the Cap Diamant heights. The outline of the rampart for the temporary citadel is still visible on the Plains. Martello towers 1, 2 and 4 are still standing proudly in Québec City and are used by the National Battlefields Commission for heritage interpretation and period presentations. Finally, the citadel marks the eastern boundary of the Plains and is used for historical interpretation and, still, as a Canadian Forces base.

You may also like

The Martello Towers of Québec City

Iconic structures on the Plains of Abraham, the Martello Towers of Québec City were built between 1808 and 1812 as the walled city’s first line of defence.