In late summer 1775, two groups of American revolutionary soldiers set off on a campaign to capture Québec City. With the aim of freeing Canada from the British yoke, specifically the colony of the Province of Quebec, the troops under General Richard Montgomery passed by Lake Champlain and followed the Richelieu River, while those under Benedict Arnold followed the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers in much harsher conditions.

In November 1775, the troops disembarked near the Plains of Abraham. This initial siege would culminate in the Battle of Quebec, on the blizzardy day of December 31, 1775.

Beginnings of the American War of Independence — 1775

When the American War of Independence began, the Seven Years’ War had barely ended a little more than a decade earlier with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. This treaty gave Great Britain a territory that had been known as New France for over 150 years.

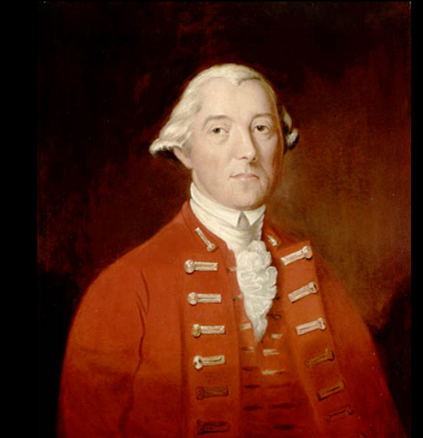

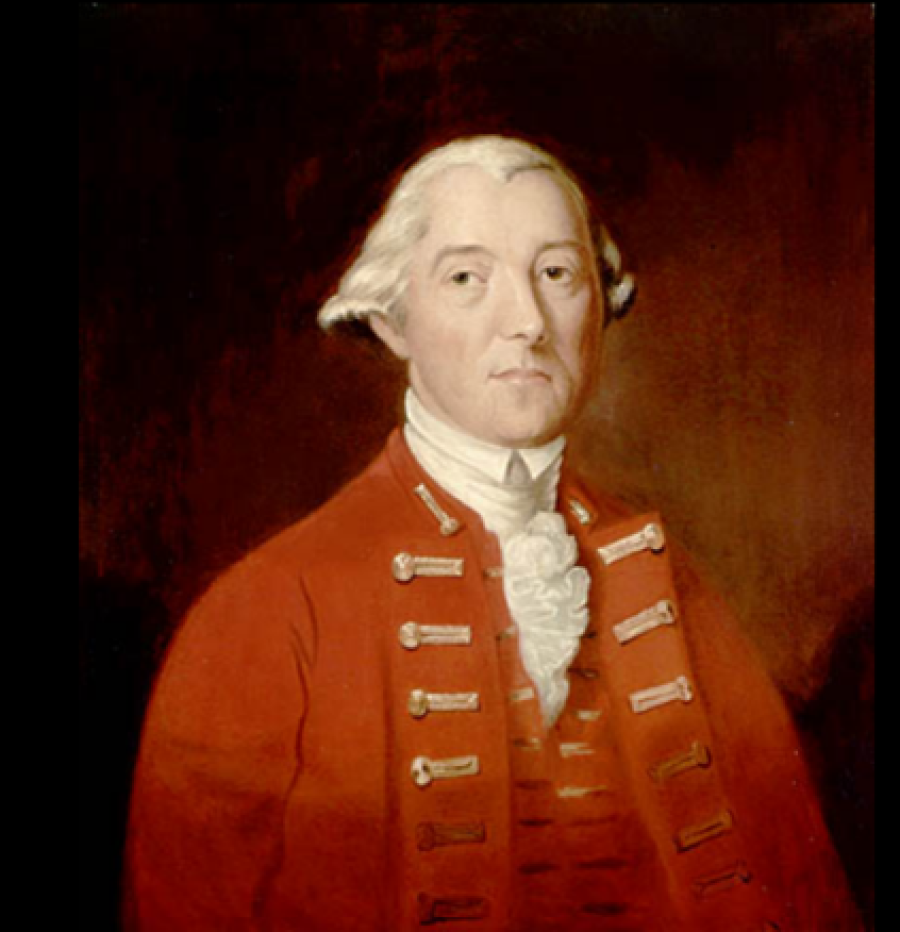

Governor Guy Carleton, hoping to win the support of the inhabitants of the Province of Quebec, adopted a policy of tolerance toward the Catholic faith, notably by restoring the use of French Civil Law. This was in the Quebec Act, voted by the British Parliament in 1774.

Meanwhile, discontent was growing in the Thirteen Colonies. Great Britain had brought in new taxes to pay for the expenses of the last war. Also, by greatly increasing the province’s territory, the Quebec Act thwarted the territorial ambitions of the colonies next to Quebec, as well as the ambitions of land speculators.

For these reasons, and also because they no longer needed Britain for defence against the French, the American colonies came together in the Continental Congress and called for revolution.

Expedition to Québec City

On learning about the intentions of the Continental Congress, the British governor Guy Carleton proclaimed martial law and mustered a small force of militia volunteers. In Québec City, preparations were made for the Americans’ arrival. The gates of the city now closed at 6 p.m., and non-residents had to announce their entry. Food was stored for a siege that might last until spring. Houses were burned down to eliminate places where revolutionary soldiers could hide. The Church warned parishioners to remain loyal to the British crown. Nonetheless, the population was divided.

As early as 1774, the Continental Congress saw French Canadians as potential allies and reached out to them through letters that circulated in the Province of Quebec. The first battles took place in April 1775. On June 27, 1775, the Continental Congress approved the invasion of Canada.

A plan to take Québec City was devised. The British forces would be split by two simultaneous lines of attack.

Richard Montgomery and Philip Schuyler took the Lake Champlain route to get to Montreal. Everything went more or less according to plan, with a string of victories, but Schuyler fell ill and eventually turned the command over to Montgomery. The troops arrived in Montreal in mid-November.

Benedict Arnold followed the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers. This route took longer and proved more difficult than he had estimated. In particular, it was interrupted by rapids and very long portages. The inadequate provisions and the cold took their toll on the morale and health of the troops.

- 2 500 men for the invasion of Canada

- 1 400 under Schuyler and Montgomery

- 1 100 under Benedict Arnold

The expedition came into contact with French Canadian inhabitants and some First Nation communities, including the Abenaki of Odanak and the Penawapskewi. Some Abenaki guides provided essential assistance for the advance through this poorly known territory. Arnold’s troops were thus able to find the village of Sartigan (today Saint-Georges de Beauce) and get the food they needed to continue on their way.

After a journey lasting about two months, rather than the estimated twenty days, with a loss of a hundred or so men who had died or turned back, Arnold finally reached the south shore that faces Québec City. In the night of November 13 to 14, his forces crossed the river and, at Anse-au-Foulon, climbed the cliff up to the Plains of Abraham. Some of his soldiers set up their quarters in the Hôpital-Général de Québec, in the Lower Town near the city’s walls. The nuns had to share their premises with them.

Arnold demanded the surrender of the city as soon as he arrived, but to no avail. Because his men were starving and weakened, he pulled back to the west and waited for Montgomery’s army, which finally arrived in early December.

- Over 1000 American soldiers on the Plains of Abraham

- 1 650 soldiers on the British side to defend Quebec City

- 357 soldiers of the regular army

- 450 sailors

- 543 Canadian militiamen

- 300 English-speaking militiamen from the garrison

Siege of 1775

On December 4, several American companies took up position on the Plains of Abraham and at certain locations in Québec City’s suburbs. Governor Carleton was again called upon to surrender the city, and again in vain. No reply was even given.

On December 9, the Americans began to bombard Québec City from their artillery batteries on the Plains of Abraham, in St. Roch, and at St. John’s Gate.

A winter siege is different from a typical campaign and requires its share of adjustments, as the troops discovered the week of December 8 to 14 when setting up a battery on the Plains of Abraham.

The soil was icy and too hard. The soldiers could neither dig trenches in it nor use it for earthworks. Instead, they had to fill the structures with snow or with water that would freeze. A few days later, this earthwork substitute would prove to be inadequate and much less solid.

The British were not the only enemy of the Americans. In addition to artillery attacks, the latter had to deal with smallpox, which was claiming more and more lives. The soldiers feared infection so much that many inoculated themselves, despite the ban on doing so from their officers. Many caught smallpox, since the infected did not isolate themselves.

Attack of December 31, 1775

Before dawn, on December 31, the American troops were getting ready. Montgomery envisioned actions on two fronts. First, there would be attacks in the Upper Town, on Cap Diamant, and at St. John’s Gate. These were feints to distract the other side. The real attack would be in the Lower Town, from the north and the south simultaneously.

Montgomery attacked from the south, along the base of Cap Diamant. His troops struggled to advance between the huge blocks of ice cast ashore by the tide and the biting wind. They managed to move forward, but were soon spotted near Place Royale. Montgomery was fatally wounded, and his men withdrew shortly after.

Arnold was in charge of the attack from the north, through Saint-Roch. His detachment was composed of American, French Canadian, and First Nation combatants. A cannon was transported on a sled, but it got stuck in the snow and had to be abandoned. With the British firing from the ramparts, his troops then followed the cliff near Sault-au-Matelot. Arnold was wounded in a leg during the assault and had to go to the rear for treatment. The British, realizing that the Upper Town attack was a ruse, cornered and captured the rest of the men.

Around 10 a.m., the British declared victory. This was the first American defeat in the War of Independence.

Siege of 1776

427 prisoners, including 32 officers

The British remained in the city and awaited an American withdrawal. The soldiers captured during the battle of December 31 were sent to the Quebec seminary and the Récollet monastery. Some tried to escape.

Outside the walls, the siege continued. Arnold managed to set up batteries at Pointe-Lévy, near the Saint-Charles River and on the Plains of Abraham in early April. Smallpox was still taking its toll on the soldiers.

In early May, the situation changed with the arrival of boats bringing British reinforcements. The captured Americans were freed, and the American troops lifted their siege and retreated on May 6, 1776. Over the following days, the last of the revolutionary forces abandoned their positions in the province and fell back to New York.

To maintain order and prevent a new invasion attempt, the British called in German soldiers, with more than 4,000 of them arriving at the port of Quebec in early June. They were followed by thousands of others and would play a significant role in defending Canada during the rest of the war.

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris brought the American Revolution to an end. The independence of the United States was therein recognized, and the new country’s borders defined.

Today, on the Plains of Abraham, vestiges of that time can still be seen in the temporary citadel atop Cap Diamant and a blockhouse built nearby.

![Sydney Adamson (1903). Carrying the bateaux at Skowhegan Falls [gravure par C.W. Chadwick]. Library of Congress](https://ccbnwebprod.blob.core.windows.net/website/Histoire-et-patrimoine/Occupation-civile-et-militaire/Invasion-1775/_900xAUTO_fit_center-center_100_none/Image2_2025-02-24-172656_befi.png)