The life of Marie-Josephte Corriveau

Born in 1733 in Saint-Vallier, Marie-Josephte Corriveau married for the first time in 1749, at the age of 16. Charles Bouchard was a militia member during the Seven Years’ War and fought notably on the Plains of Abraham in September 1759. Marie-Josephte bore three children during this first marriage: Françoise, Angélique and Charles.

In April 1760, Charles Bouchard died of “putrid fever,” a term used at the time to describe a contagious and often deadly condition, with symptoms including a high fever, chills and a rapid heart rate.

Widowed, Marie-Josephte had to ensure the future of her family while also caring for her parents. In 1761, she married Louis-Étienne Dodier, the owner of the land adjoining hers. However, Joseph, Marie-Josephte’s father, and her new husband did not get along at all, and several altercations occurred between the two men.

It seems that the couple’s relationship was also troubled. In 1762, Marie-Josephte fled the home to seek refuge with her uncle. She was forced to return to the family home by Major Abercrombie, the military officer in charge of maintaining order in the region. The residents of Saint-Vallier, as well as the British authorities, were well aware of the tensions between Dodier and Marie-Josephte, as well as between Dodier and Joseph.

On January 27, 1763, Louis-Étienne Dodier was found dead in his stable. A report was quickly drafted, with witnesses, establishing that horse kicks were the cause of death. He was buried the same day with the consent of Major Abercrombie.

It is easy to understand that this event caused quite a stir in Saint-Vallier. Dodier had been buried very quickly, without displaying the body, and all this in the midst of ongoing family feuds. Rumours circulated that either Joseph Corriveau or his daughter were responsible for his death.

A few days later, Dodier’s brother filed a complaint asking for justice to be done, as he was convinced that elements related to the death had been concealed. Sergeant Alexander Fraser also informed Abercrombie that he had gone to the barn on the morning of January 27 and that the injuries he had seen on the deceased’s face could not have been caused by horse kicks. Abercrombie notified Governor Murray, who ordered the body to be exhumed. An autopsy confirmed the information.

Joseph Corriveau and his daughter Marie-Josephte were arrested by the British authorities and detained in Québec City.

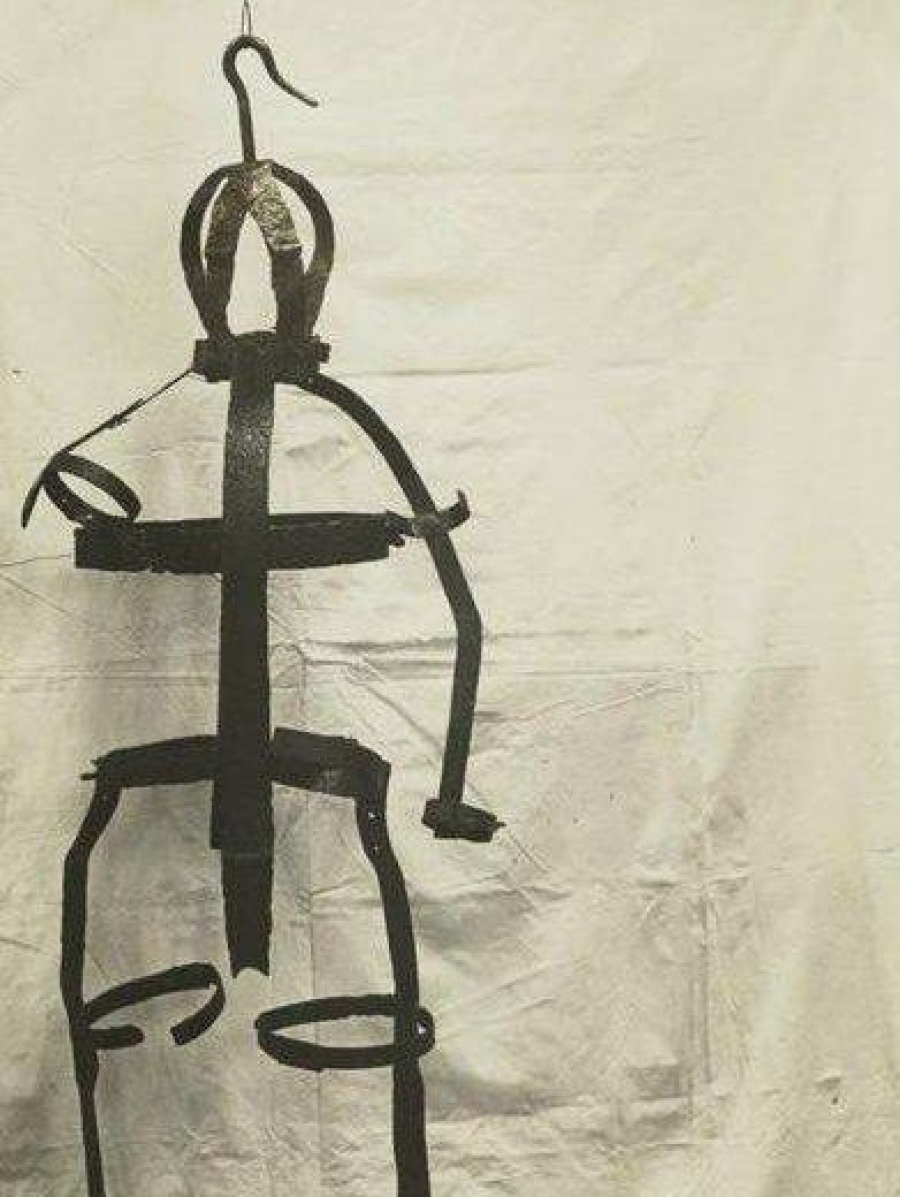

Illustration: Edmon-Joseph Massicotte

Court-martial trials

Since 1760, the province of Quebec had been under British military rule, so the trial took place in a military context. News of the Treaty of Paris—signed on February 19, 1763, officially ceding New France to the British—would not reach the colony until May.

With much of Québec City still in ruins after years of bombardment, Marie-Josephte Corriveau’s first trial was held at the Ursuline Convent, from March 29 to April 6, 1763, before a court-martial likely made up of members with limited understanding of French. There is no evidence that any interpretation was provided for the testimony.

- 2 accused

- 12 English officer-judges

- 25 witnesses

The two accused, Marie-Josephte and her father, were defended by lawyer Jean-Antoine Saillant, which marked a departure from French legal practices under which accused parties were not permitted legal representation. A number of witnesses were heard, including Marie-Josephte’s two daughters. Parish priest Blondeau and militia captain Jacques Corriveau suggested they had tried to protect the Corriveau family’s honour by describing the death as accidental. Testimony also revealed that Dodier had suffered four wounds, evenly spaced on his face.

The verdict was delivered on April 9. Joseph Corriveau was sentenced to death for the murder of his son-in-law, Louis Dodier. His daughter was found guilty of being an accomplice. The execution was scheduled for April 15.

As was customary, Joseph Corriveau was allowed to confess before his execution. He told Jesuit priest Glapion that he had taken the blame in order to save his daughter. Wracked with guilt and fearing he might be denied entry to heaven, he named Marie-Josephte as the sole perpetrator. Informed of the confession, Governor Murray ordered a second trial, which began—and concluded—on April 15. Joseph Corriveau was acquitted. In the meantime, Marie-Josephte is said to have confessed; she pleaded guilty.

Hanging on the Plains

On April 18, 1763, Marie-Josephte Corriveau was taken from the prison in the Redoute Royale to be hanged at a place known as the Buttes-à-Nepveu, near what is now the Plains of Abraham Museum. Many curious onlookers likely gathered, as was common for public executions at the time.

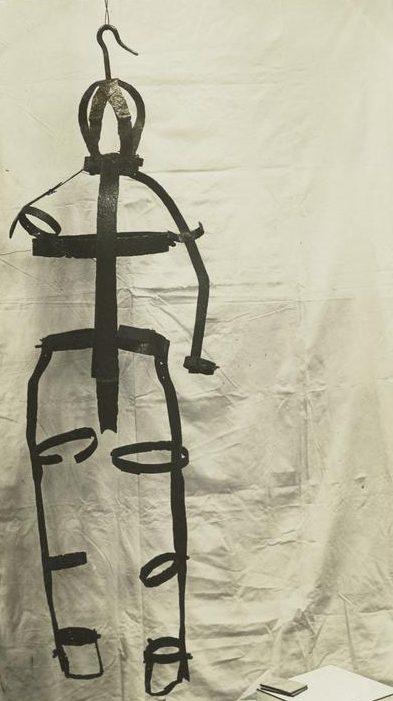

As per the orders of Governor Murray, her corpse was then placed in an iron gibbet cage made to fit her body, before being transported across the river to Pointe Lévy, where it was put on display in a busy public area, hung from a gallows. It would remain there for more than a month.

In the province of Quebec, this punishment was unprecedented, although it was more common in English territories, especially in the decades prior. Rising crime rates had led British authorities to impose harsher sentences. The public nature of the punishment was intended to serve as a deterrent, to inspire fear. As added deterrence, the body was not typically returned to the family, thus denying the usual religious rites.

On May 25, 1763, news of the end of the war reached Québec City. With “peace made,” Governor Murray authorized the removal of the cage. Marie-Josephte Corriveau was buried in the cage, near the Church of Saint-Joseph-de-la-Pointe-Lévy.

“La Corriveau” becomes a legend

With such an unusual punishment, it is easy to see how the story of Marie-Josephte Corriveau left a lasting impression, stoking fears and remaining part of the oral tradition in the Côte-du-Sud region for decades after.

The story of Marie-Josephte Corriveau, the widow Dodier, gained widespread attention around 1850, when the cage was accidentally rediscovered. Author Louis-Honoré Fréchette played a key role in bringing it to light, claiming to have witnessed the exhumation of the cage near Saint-Joseph Church.

The cage became a subject of curiosity. It was displayed in various locations, including Montréal and Québec City. To attract visitors, newspapers published sensational details, often with little regard for historical accuracy. As early as 1851, with an article in the La Minerve newspaper, the story began to drift from the truth. She was said to have killed two husbands by pouring molten lead into their ears, while Dodier was rumoured to have been strangled, then struck with a hammer before having his skull pierced with an iron fork. In the press and in books, Corriveau morphed into a legend. The number of husbands she had supposedly killed multiplied, and it was said that she poisoned them. The tale of La Corriveau, the witch, spread far beyond the Côte-du-Sud.

The cage was exhibited in a few locations in the United States before finally ending up at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. In 2011, members of the Société d’histoire régionale de Lévis noticed it at the museum. Marie-Josephte Corriveau’s cage was subsequently returned to Quebec for analysis and to confirm its authenticity. It is now part of the collection at the Musée de la civilisation.

More than 250 years after her death, the story of Marie-Josephte Corriveau continues to captivate. Numerous works have been inspired by her legend and life. Among them is the theatrical performance Sur les traces de la Corriveau, which has been staged annually since 2013 in the town of Saint-Vallier. This collaboration between the National Battlefields Commission and the local municipality involves dozens of actors and extras.

More recently, she was also portrayed by artist Jérôme Trudelle in the Aeria exhibition at the Plains of Abraham Museum from 2022 to 2024.

Visuals:

Massicotte, Edmon-Joseph. Illustration by Edmond-Joseph Massicotte for the short story "Une relique" (A Relic) by Louis Fréchette, in Almanach du peuple Beauchemin pour l'année 1913. 1912, Montréal.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. Gibbet used in St. Vadier near Quebec in 1763 for the body of Mdme. Dodier hung for murder of her husband. 1860 - 1920, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Julien, Henri. François Dubé with "La Corriveau".Sketch by Henri Julien for Les Anciens Canadiens by Philippe Aubert de Gaspé, 1916, Montréal.